Warsaw, Poland

By the beginning of the 20th century, the idea of confinement to a ghetto as a way of life for Jews had been all but abolished. However, the concept was reintroduced and took on a whole new meaning under the Nazi regime of Adolf Hitler. In the Third Reich, the ghettos of Europe went from being thriving Jewish neighborhoods to virtual prisons from which Jews were organized and ultimately deported to the various concentration camps. There were over a dozen major ghettos and countless smaller ones, the majority of which were located in Poland. Of these, none are as famous as the ghetto of the city of Warsaw, whose inhabitants fought against their oppressors in one of the most desperate and heroic uprisings of the war. The Historic Center of Warsaw is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

History

At the outset of World War II, Poland, which was home to Europe’s largest Jewish population, had the bad luck of being Germany’s next-door neighbor and prime target. The Germans invaded in September of 1939, and barely a month later it was over. In the aftermath of Poland’s disastrous defeat, the Nazis went to work implementing Hitler’s plans for the Jews. Because Poland’s Jewish population was much larger than anything the Nazis had to deal with in Germany, Austria or Czechoslovakia, new measures had to be conceived to keep the Jews under close supervision.

The initial measures focused on the concentration of the Jewish populations into the existing ghettoes of the major cities, such as Warsaw and Krakow. The ghetto of Warsaw, the largest in pre-war Europe, was home to more than four hundred thousand Jews, almost forty percent of the city’s population. In November 1940 the Nazis built a wall around the ghetto and began relocating Jews from the surrounding countryside there. Perhaps another fifty to one-hundred thousand were added to the existing population. To say that life in the ghetto under the Nazis was difficult is an understatement. The community was rampant with starvation, disease and violence. As many as a hundred thousand Jews died in the ghetto just from these tribulations.

In the summer of 1942, the Nazis began liquidating the Jews of the ghetto. In two months approximately seventy-five percent of the population was shipped off to the Treblinka death camp. The remaining Jews, realizing that the deportations were to end in their annihilation, decided to fight back. In January 1943, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began under the leadership of Mordechai Anielewicz. Less than a thousand Jewish resistance fighters, poorly armed and with only minimal support from the outside, took on the German army and the SS.

Despite the overwhelming odds against them, the Jewish uprising lasted for the better part of four months. They even had some initial successes against the Germans. By April it was clear to the German commanders that it would take a substantial military effort to overcome the ghetto insurgency. In the end, they decided it was easier to destroy the entire ghetto block-by-block with explosives and flamethrowers. By May 16 it was all but over. More than ten thousand Jews died during the uprising, and almost all of those who survived were subsequently killed at Treblinka. Some escaped to join with the Polish resistance and even fought again in the much larger Warsaw Uprising of 1944. By the time the war ended, virtually all of Warsaw had been destroyed. Few traces of the once flourishing Jewish community remain in Warsaw today.

Visiting

What used to be the Jewish Ghetto in Warsaw was completely destroyed during the war, along with eighty percent of the rest of the city. However, the city’s current Muranow district, located where the ghetto used to be, preserves a number of sites related to the uprising and to the Jewish community before the war. The most important site related to the uprising is the Monument of the Ghetto Heroes. This large stone edifice marks the loction of the uprising’s command center and commemorates the leaders of the valiant but ultimately doomed effort.

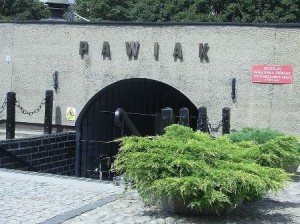

The Pawiak Museum, part of the Warsaw Museum of Independence, stands on the site of a former 19th century prison. This prison, destroyed by the Germans towards the end of the war, was used by the Nazis to round up and deport many Jews and other undesirables from Warsaw. Nearly forty thousand Jews were killed on the site, and countless others sent off to concentration camps from here. The museum commemorates this atrocity as well as the brutal history of the prison before the war.

The Pawiak Museum is located on the northwest side of Warsaw, about a half mile west of the old city. It is open Wednesdays from 9:00am-5:00pm; Thursdays and Saturdays from 9:00am-4:00pm; Fridays from 10:00am-5:00pm; and Sundays from 10:00am-4:00pm. Admission to the museum is by donation. Web: www.muzeumniepodleglosci.art.pl (official website)

Other Sites

The Jewish community of Warsaw, which once numbered in the hundreds of thousands, has since dwindled to a mere few hundred. That did not stop them from rebuilding the Nozyk synagogue, the only synagogue still standing in Warsaw. There is also a small memorial in the city’s Umschlagplatz commemoratinig the location where hundreds of thousands of Jews boarded the trains that took them to the death camps. Several other related places of interest include the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, and the Museum of the Warsaw Uprising. There is a Mordechai Anielewicz Memorial in the city of Wyszkow, which may or may not be the site of the hero’s grave.

Leave a Reply